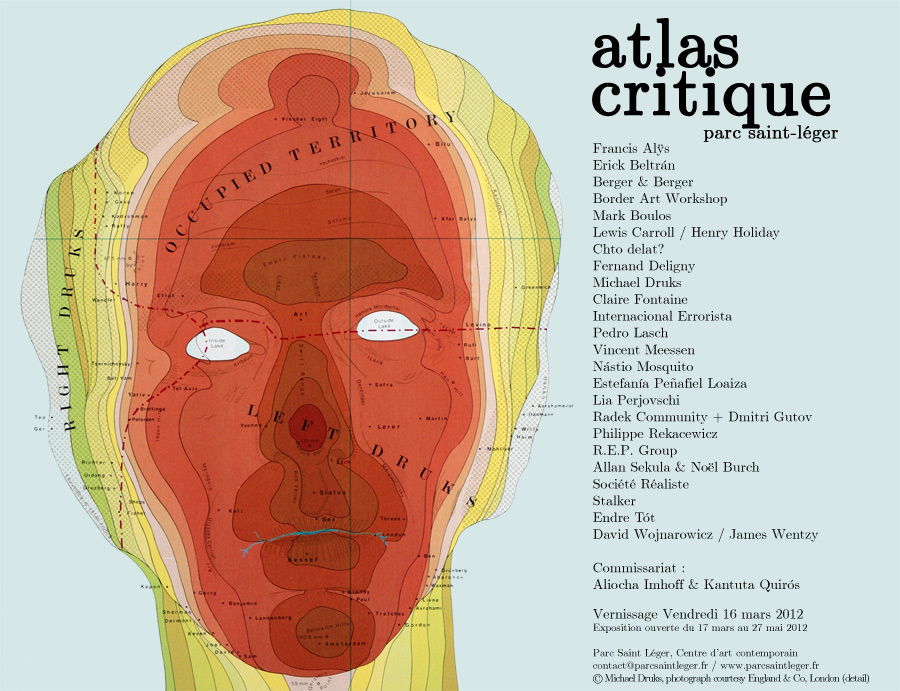

Atlas critique

Exhibition

Le Parc Saint Leger, Centre d’Art Contemporain, invites le peuple qui manque.

Francis Alÿs, Erick Beltrán, Berger & Berger, Border Art Workshop, Mark Boulos, Lewis Carroll / Henry Holiday, Chto delat?, Fernand Deligny, Michael Druks, Claire Fontaine, Internacional Errorista, Pedro Lasch, Vincent Meessen, Nástio Mosquito, Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza, Lia Perjovschi, Radek Community + Dmitri Gutov, Philippe Rekacewicz, R.E.P. Group, Allan Sekula & Noël Burch, Société Réaliste, Stalker, Endre Tót, David Wojnarowicz /James Wentzy / AIDS Community Television.

Curators : Aliocha Imhoff et Kantuta Quirós

Opening : Vendredi 16 mars 2012 à 18h30

Dates: March 16, 2012 – May 27, 2012

Parc Saint Léger, Centre d’art contemporain

Avenue Conti 58320 Pougues-les-Eaux / France

“The ‘new critical thoughts’ are an unknown continent, in the process of formation, since the historical defeat of Marxism as a thought and as a movement has ushered in a new era – in which Marxism is present, but in a different mode than before – whose coordinates are still unknown to us. Hence the importance of multiplying and confronting maps.” (Razmig Keucheyan, 2010)1

At a time when critical thought and contemporary politics are mutating and redeploying themselves, the need has arisen to establish new cartographies of this theoretical continent in formation. Atlas, cartography and diagram, by spatializing forms and modes of thought and critical intellectual work, offer us an optimal visuality. The atlas, as a visual form of knowledge presentation, is said by art historian Georges Didi-Huberman to be designed to capture the fragmentation of the world and “reassemble the world “2. By dismantling and reassembling old categories, by establishing invisible connections and links that had hitherto remained unintelligible, the atlas proves to be the ideal operating model for establishing and proposing synoptic tableaux that would link conceptual archipelagos, world images and political constellations. The diagrammatic thinking of Erick Beltran (Mexico), Lia Perjovschi (Romania) and Vincent Meessen (Belgium) is part of this archaeology of knowledge, while offering forward-looking models of the geography of contemporary critical theories. Their conceptual landscapes, with their strong interweaving of the subjective and the systemic, constitute imaginative encyclopedias, machines of transformation.

All that is solid melts into air

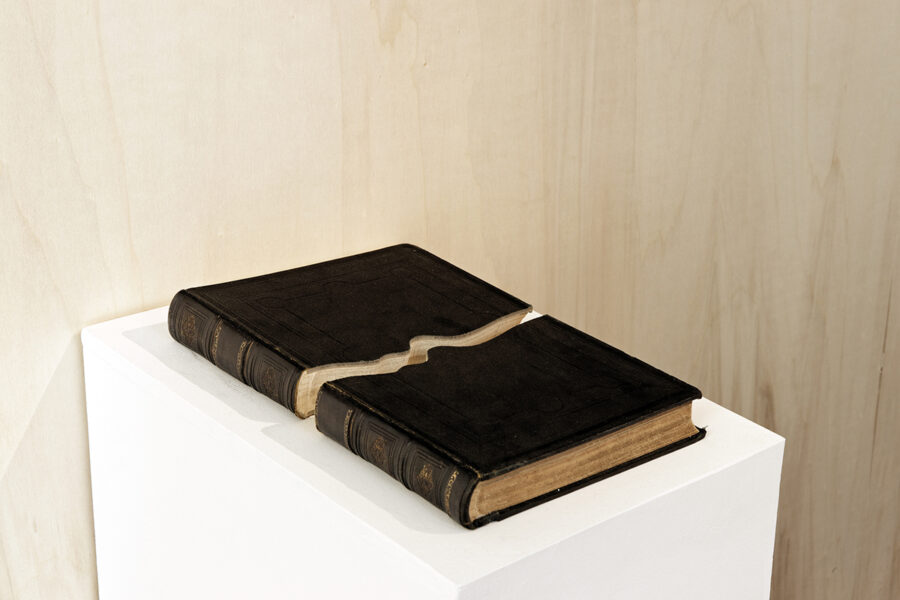

But even more than this, at a time when for many contemporary theorists, geographers and political philosophers (Edward Soja, Fredric Jameson or David Harvey), space dominates time, many geographical concepts, such as cartography, scale, frontier, distance or territory, are proliferating in the field of art, and a resurgence of interest in thinking about space has occurred recently, well beyond geography, architecture or urban planning. Critical theory and the social sciences now appeal with renewed insistence to spatialities to read social phenomena. Capitalism, itself long considered without territory or frontiers, is now thought of as a phenomenon that engages in spatial planning when it invests a territory. For geographer David Harvey3, capitalist crises are physically embodied in the spaces they produce. In his striking diptych All that is solid melts into the air4 (2008), artist Mark Boulos plays with proximity and distance in a dialectical montage. By pitting rebels from the Niger Delta against traders from the Chicago Energy Exchange, on the first day of the subprime crisis, Boulos reveals the causal spatialities between financial speculation and the dispossession of Nigerian workers, through the global circulation of a material that has become immaterial value: oil. “Money does not yet exist, the commodity does not yet exist, the whole symbolizes the ‘metaphysics of capitalism’. With The Forgotten Space (2010), the latest film by artist Allan Sekula and filmmaker and film theorist Noël Burch, these two experimenters in the documentary genre consider the sea as the forgotten space of these globalized times, a place of exchanges and all circulations within the globalized economy.

B/orderlands 5

Theorists of postcolonial thought have also produced spatial analyses of the ideological construction of notions of border and distance. “People who live on a few acres will draw a border between their land and its immediate surroundings and the territory beyond, which they call ‘the land of the barbarians’. (…) Every era and every society recreates its own Others “6 , wrote the Palestinian intellectual Edward Saïd, who described this phenomenon as a “dramatization of distance”. The extent to which toponymy, the geographical naming of territories (in the Americas, for example) or of “near” and “far” (us and the others, the center and the periphery, the national space and the rest of the world, or the Near/Middle East) correspond to epistemic categories, underpinned by the question of who has the power and authority to name and subsume Others within identity categories. Postmodern anthropologists (James Clifford, Johannes Fabian) and radical geographers (Derek Gregory), nourished by postcolonial theory, have also shown that the distancing of “the Others” is the result of imaginary geographical constructions that extend – far beyond the physical and symbolic borders that structure continents, countries and cities – right down to the disciplines of knowledge7. These hegemonic systems of spatial and geographical meaning are now being rewritten by contemporary artistic practices. Thus, while we know how deeply cartography, as a discipline, was involved in the performative production of the narratives of modernity, rationality and positivism, but also of the history of colonialism and national narratives, today it has become the privileged site for the invention of counter-practices and counter-mapographies by artists, which open up lines of escape.

The zero meridian

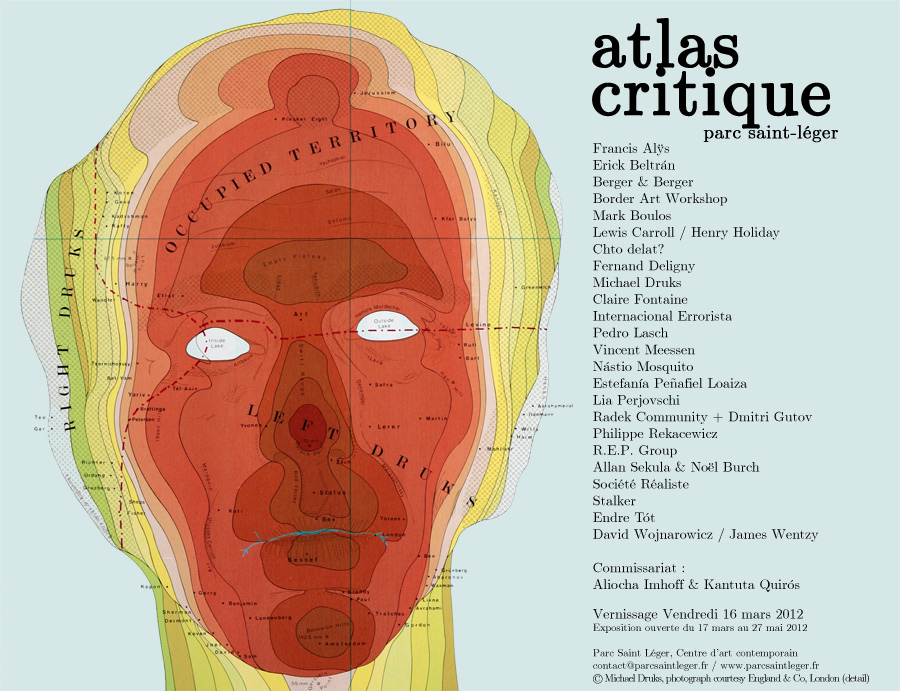

In the course of the 19th century, the acceleration of colonial ventures by European countries – which had already taken off in the 15th century with the gradual mastery of sea routes and the colonization of the American continent – led to a territorial expansion which, right into the interior of continents and in the extreme regions of the globe, reduced the blank spaces on maps while refining their precision even further. Cartography became not only an instrument for territorial and military appropriation, but also an imperialist ideological matrix. Thus, the homogenization of temporal measurements, through the promulgation of the Greenwich meridian in 1884 as the universal tuning fork of time, imposed an implicitly Eurocentric universalism. With the choice of the zero meridian, this manufacture of universal time was a function of spatial warfare8. It was against this backdrop that Lewis Carroll and illustrator Henry Holiday’s blank, hollowed-out map of the ocean appeared in the short story The Hunt for the Snark, published in 1876. This ideal map of the ocean, stripped of terrestrial conventions and landmarks, could be described by literary theorist Bertrand Westphal as a “paradoxical map, (…) from which a space of freedom might emerge “9 , conjuring up an imaginary of conquest, yet tinged with a nostalgia linked to the end of virgin spaces10.

Upside Down – América Invertida

In 1943, Upside Down / América Invertida, the famous drawing of a map of South America “upside down” by Uruguayan artist Joaquìn Torres Garcìa – representative of the “School of the South” pictorial movement – inverted the representation of the Northern and Southern hemispheres and political, cultural and geo-epistemic hierarchies. Today, a young generation of artists sees Ecuador, the sign of North/South partitions, as a place for rewriting. Ecuadorian artist Estefania Peñafiel Loaiza and Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão present it as a contingent line that arbitrarily truncates postcolonial bodies and subjects. And cartographer and geographer Philippe Rekacewicz (FR), artist/videographer/performer Nástio Mosquito (Angola), collectives Société réaliste (FR), Claire Fontaine (FR), Stalker (Italy), who are interested in displacements, mobilities and migrations, and other nomadic geopoetics, question, more broadly, through disruptive spatialities, North/South epistemologies and hegemonies, the constructivism of borders and national fictions. A new physics of the map is born.

Places-real-and-imagined

“A border is a vague, indeterminate place created by the emotional residue of an unnatural boundary. The border between the United States and Mexico is an open wound where the Third World rubs shoulders with the First and bleeds. Open wound 1950 miles long / dividing a pueblo, a culture, running the length of my body, planting fence posts in my flesh / cuts me in two in two / cracks me up cracks me up.” Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands – La Frontera – The New Mestiza (1987) 11

Chicano theorists, writers and conceptual artists (Border Art Workshop, Pedro Lasch, Gloria Anzaldúa) have challenged the naturalness of the Mexican-American border, seeing it simultaneously as wall and passage, suture and break, boundary and threshold between worlds, site of oppositional culture and political struggle. With his major and internationally acclaimed book, Borderlands / La Frontera: The New Mestiza (1987), Gloria Anzaldúa, Chicana poet and theorist of post-colonial and post-feminist studies, envisioned borderlands as liminal spaces at the origin of a new geography of self and knowledge, inaugurating a theory of knowledge based on radical disidentification, loss of control, a space of in-betweenness, where the writer becomes a visionary cultural worker, moving between often conflicting worlds. Anzaldúa’s multilingual methodology embodies what Walter Mignolo calls “frontier thinking”, a double consciousness employing multi-language to offer a new epistemology. Following in the footsteps of the Chicano Art Movement, which emerged in the United States in the 1970s, the Border Art Workshop (BAW) / Taller de Arte Fronterizo (TAF) collective has been working on the political, cultural and imaginary topos of the border since 1985, through site-specific actions on the Mexican-American border. While the Chicano Art movement had already asserted the notion of border culture, and posited Spanglish as a poetics of cultural hybridization, the emergence of BAW / TAF coincided with the enactment of new migration laws in the United States and an industrial intensification of the border.

Around the exhibition

– Wednesday May 16 at 7pm: performance by Olive Martin & Patrick Bernier: “X. c/Préfet…, Plaidoirie pour une jurisprudence” at the Palais ducal, salle du conseil municipal, Nevers – Saturday April 21 at 8:30pm: screening of the documentary “Qu’ils reposent en révolte” (2011) by Sylvain Georges at the Auditorium Jean Jaurès, Nevers, in partnership with ACNE

– Saturday April 14 at 5:30pm: conference-debate with Giovanna Zapperi and Razmig Keucheyan at Café Charbon, Nevers

This exhibition would not have been possible without loans from: Fondation Antoine de Galbert, galerieofmarseille, Galerie Michel Rein, Sandra Alvarez de Toledo, Christine Konig Gallery, England Gallery, Galerie Alain Gutharc, Fonds Départemental Nouveaux Collectionneurs – Conseil Général des Bouches-du-Rhône, David Zwirner Gallery, Rosascape, Doc Eye.

Acknowledgements

Parc Saint Léger (Sandra Patron, Ronan Le Pennec, Vincent Valéry, Franck Balland, Fanny Martin, Léa Mérit, Céline Poulin, Jean-Philippe Darini), L’Arachnéen (Sandra Alvarez de Toledo, Anaïs Masson), Fondation Antoine de Galbert (Arthur Tocqué), Aude Lavigne (France Culture), BAW/TAF (Michael Schnorr), Francis Alÿs and David Zwirner Gallery (Maggie Bamberg, Erin Caroll, Stephanie Stockbridge), Erick Beltran and Labor (Niki Nakazawa), Berger & Berger, Bertrand Westphal, Alexandra Baudelot (Rosascape), Mark Boulos, Michael Druks and England Gallery (Jane England), Dmitry Vilensky (ChtoDelat? ), Claire Fontaine (Fulvia Carnevale and James Thornhill), Federico Zukerfeld, Galerie Alain Gutharc (Laure Saucias), Pedro Lasch, Vincent Meessen and Saskia Ooms (Netwerk), Nástio Mosquito, Estefanía Peñafiel Loaiza, Lia Perjovschi and Christine Konig Gallery, Radek Community + Dmitri Gutov, Philippe Rekacewicz, R.E.P. Group, Allan Sekula & Noël Burch, Galerie Michel Rein (Angharad Williams), Société réaliste (Ferenc Grof and Jean-Baptiste Naudy), Stalker (Francesco Careri) Giovanni Careri, Endre Tót, Jim Hubbard, James Wentzy, Sylvain George, Yannick Gonzalez (galerieofmarseille), Fonds Départemental Nouveaux Collectionneurs – Conseil Général des Bouches-du-Rhône, Doc eye (Joost Verhay), Patrick Bernier and Olive Martin, Razmig Keucheyan, Giovanna Zapperi, Stephen Wright, Anne Querrien, Teresa Castro, Anna Knight

Footnotes

1 In Nouvelles pensées critiques? Interview with Razmig Keucheyan and François Cusset, revue Contretemps n°8, 2010 2 Georges Didi-Huberman, Atlas ou le gai savoir inquiet, L’Œil de l’histoire 3, 2011, Les Editions de Minuit, Paris 3 Read David Harvey, Géographie et capital. Vers un matérialisme historico-géographique, Syllepse, 2010 and David Harvey, Géographie de la domination, Les Prairies Ordinaires, 2008 4 Mark Boulos’ film All that is solid melts into the air (2008), presented as part of the exhibition, borrows its title from Karl Marx’s 1848 phrase from The Communist Manifesto: “Everything that is solid dissolves into air.” 5 In Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. 1996, postmodern geographer Edward Soja takes the expression Borderlands from Chicana writer Gloria Anzaldúa’s book of the same name, Borderlands – La Frontera – The New Mestiza (1987), San Francisco, Aunt Lute Books, 1999. In his analysis of Anzaldúa’s book, he sees border disturbances as simultaneously attacks on public and political order, and proposes the expression (b)orderlands. 6 Edward W. Saïd, L’Orientalisme : l’Orient créé par l’Occident, Translated from the English by Catherine Malamoud, Paris, Seuil, 2005, p 90 7 On this subject, read texts by Canadian geographer Derek Gregory, including Geographical Imaginations. Oxford: Blackwell, 1994 and Violent geographies: fear, terror and political violence (2007, New York: Routledge). Derek Gregory shows how the human sciences, such as geography and anthropology, do not escape ideological uses of distancing themselves from the Other, particularly in the context of contemporary orientalism and imperialism, and what he describes as the “new colonial wars” waged after September 11 in the Middle East and Central Asia. Following the postcolonial theorist Edward Saïd, Gregory uses what he calls “imaginative geographies” to identify strategies that produce cultural difference and transform it into irreducible distance, making the conduct of military operations in the Middle East acceptable and legitimate. In his major book, Le temps et les autres. Comment l’anthropologie construit son objet, French translation by Estelle Henry-Bossoney and Bernard Müller. Toulouse, Anacharsis, 2006, postmodern anthropologist Johannes Fabian also shows how modern anthropology, after abandoning an overtly colonial attitude, has continued to maintain what Fabian calls allochrony with the peoples studied (once described as primitive), a distance that sends them back into a time (and correlatively a space) other than their own. 8 We need only recall the competing struggles between France and the United Kingdom at the Washington International Conference in 1884 over the respective imposition of their own meridian. “Bertrand Westphal writes in La géocritique, Réel, fiction, espace, Les éditions de Minuit, Paris, 2007, p. 99 9 “The map no longer serves to square the full, but to discover the void, the hollow from which a space of freedom might emerge. In all cases, it is a paradoxical cartography”, in Bertrand Westphal, La géocritique, op. cit. 10 “No more of these great voids on maps of Africa, no more pale-tinted whites, no more of these vague designations, which make cartographers despair.” Jules Verne, Robur-le – Conquérant, Paris, Le Livre de Poche, 2004, p. 52 11 Gloria Anzaldúa, Borderlands – La Frontera – The New Mestiza (1987), San Francisco, Aunt Lute Books, 1999, p24 12 This expression is used by Edward Soja, in Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. 1996 13 Fernand Deligny, Groupe de recherche sur le milieu proche, “Un langage non-verbal” in Cahiers de la Fgéri, n°2, February-March 1968, quoted in Œuvres de Fernand Deligny (1913-1996), éditions L’Arachnéen, 2007, p. 659 14 Félix Guattari, Cartographies schizoanalytiques, Paris, Éditions Galilée, 1989. 15 Barbara Hooper, Bodies, Cities, Texts, The Case of Citizen Rodney King, February 1994, unpublished manuscript, quoted by Edward Soja in Thirdspace, op.cit. 16 Anne von der Heiden, 5|16|04 – 6|26|04 KW INSTITUTE FOR CONTEMPORARY ART Berlin EXHIBITION – PRIVATIZATIONS / CONTEMPORARY ART FROM EASTERN EUROPE